August 10, 2016

In

Company News

It was a breakthrough concept. Use a fleet of small, on-demand, ride-share jets to serve a network of airports and adjust the seat price to reflect each passenger’s scheduling flexibility. Oh, and confirm the trip and fare instantly.

That was DayJet’s operating plan. It was so revolutionary, even mighty Boeing was watching with concern. And with good reason.

Think about it. A passenger goes online and inputs the date and times of a desired trip from A to B, knowing that the wider the time span for departure or arrival, the lower the price. Seconds after pressing “Send,” there’s the fare and flight. No en route transfers needed, although there may be stops to board others. In other words, passengers set the trip’s timing and pricing. And by only serving small airports, ground travel logistics were quick and hassle-free.

For the carrier, delivering such a service is as complicated as a Moonshot because the variables are nearly infinite. It must ensure an airplane is available at the locations, times and dates—near or far—chosen by a variety of customers. Same for the pilots. The routing selected must be efficient yet factor in the component of a yet unknown cohort of passengers traveling on the same aircraft from and to other airports. It must be able to accommodate any weather, ATC, staffing or other unanticipated problems or delays—profitably and quickly.

To do all that requires serious computational muscle, heavy-duty algorithms and custom-designed programming. The effort addresses two interlocked halves of a system anchored in complexity science—one that manages reservations for on-demand trips and another that manages a fleet of aircraft and its support staff.

The person behind the DayJet concept was Ed Iacobucci, a Silicon Valley superstar who cofounded Citrix Systems in 1989. He drew some Citrix veterans—two of them Russian rocket scientists, literally—to the new project along with other software developers. The team then spent more than three years creating, refining and testing the system.

In 2002, DayJet ordered 239 Eclipse 500 very light jets (see photo, top) then still in development. Iacobucci calculated that even with two pilots up front, the minijet’s break-even load factor would be about 1.3 passengers. Unfortunately, he never got to prove that. The company planned to begin operations in Florida in 2006, but a struggling Eclipse was a year late in starting deliveries. DayJet eventually got 28 jets, but by then the recession of 2008 had a stranglehold on the economy. That, combined with the late start and lack of capital, ultimately resulted in the company suspending operations just one year after launch.

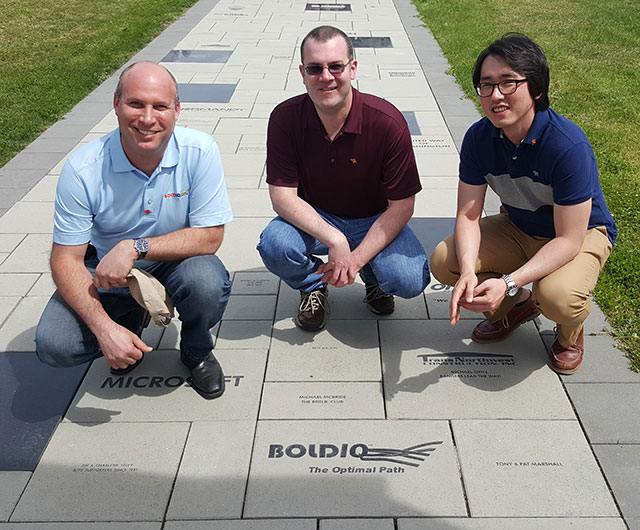

However, a group of Silicon Valley investors recognized the potential of the DayJet computer program. They purchased the technology and created BoldIQ. Based in Redmond, Washington, the 20-person enterprise is led by Roei Ganzarski, the former chief customer officer for Boeing’s Flight Services division and one who had monitored DayJet’s evolution.

Ganzarski describes BoldIQ as “a dynamic resource-optimization company” that aims to derive the best possible use of an organization’s assets “executable at the click of a button”—exactly what DayJet programmers “designed beautifully” a decade ago.

If given enough time and information, some optimization process might deliver even better results, but good, feasible, fast results are more valuable to business, Ganzarski says, paraphrasing Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.: A good plan executed now is better than a perfect plan executed next week.

Today, BoldIQ’s technology is employed by charter, fractional, managed business aircraft operators and aviation service companies, including Jeppesen, Executive AirShare, Bye Aerospace, JetSuite, Europe’s GlobeAir and New Zealand’s Merlot Aero. It also serves ground transportation providers and mobile workforce outfits by “getting the cable guy and repairman to the job” most efficiently, Ganzarski says.

Its next target is the health-care industry, with the goal of improving efficiencies to allow doctors and nurses to treat more patients.

Iacobucci died of cancer in 2013 at the age of 59. Ganzarski sees DayJet’s computerized engine as a true legacy of a man he lauds as a “software guru.” And by continuously building upon and refining that core technology, BoldIQ is “commoditizing optimization” that can benefit small and medium-size businesses.

As for those Russian rocket scientists? They’re still at it. In fact, six of DayJet’s original programmers are among BoldIQ’s employees, which is a tribute to a good idea, well executed. At the click of a key.

Click here to read the full article on Aviation Week