May 5, 2016

In

Company News

story by Sarah Murray

Few fleet managers would see attacks by bald eagles on their vehicles as a threat — that is until news emerged that Dutch company Guard From Above is training birds of prey to intercept hostile drones. However, while the birds will target unauthorized machines used in the execution of crime, legitimate commercial drones are not in their sights.

Aside from their offensive potential, drones offer a growing range of applications in the fields of security and surveillance. Much attention has focused on the possibility of drones delivering packages. But the difficulties of navigating urban areas safely means that, for now at least, there is greater commercial potential for use of drones by industries whose operations are in remote locations.

Monitoring the integrity of large, distant infrastructure such as wind farms and oil and gas installations is one task to which drones are suited. Monitoring gas flaring at oil and gasfields is one such example where drones can replace human surveillance, whether from the ground or aircraft.

“When you’ve got plants and machinery moving around, that’s where it’s ideal,” says James Harrison, co-founder and chief executive of Sky-Futures, which uses drones to inspect oil and gas installations. “They’re flying computers that can capture a lot of details and data that humans can’t, and from angles and places humans can’t get to.”

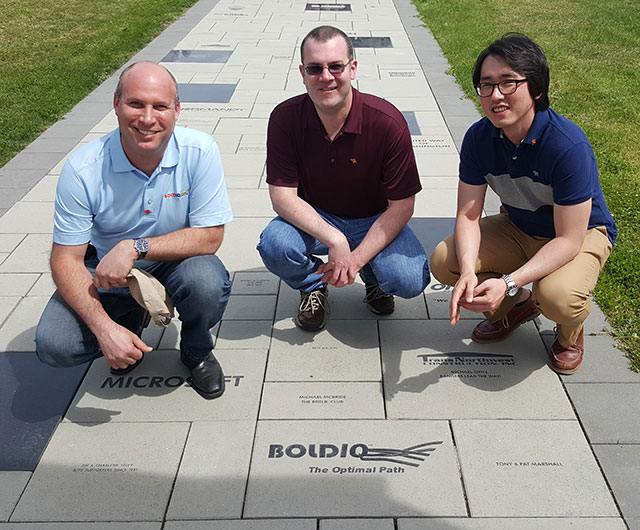

Moreover, drones do not get tired or bored. “Drones replace the individual where the job is very remote, tedious, time-consuming and prone to human error,” says Roei Ganzarski, president and chief executive of BoldIQ, whose software helps companies manage complex operations.

Drones can also help reduce the risk of fighting fires, particularly in areas prone to outbreaks such as Australia and parts of the western US, by helping crews understand more quickly the direction in which the fires are moving.

“With the smoke, you don’t want to put up a piloted aircraft,” says Mr Ganzarski. “A drone could fly into the fire and give real-time information on where to go to and where not to go to avoid risk.”

Farmers are harnessing drones’ capabilities. By flying over fields, the machines can collect accurate images of the state of planted crops, providing more detail than satellites. This allows farmers to identify areas where crops need more attention to increase yields. Using drones to spread fertiliser or pesticides across large areas of land means any accidents involve a machine rather than putting pilots at risk of injury or death in light aircraft. Across such industries, drone fleets could start to emerge as companies see the potential for the cost savings and increased safety during surveillance and other operations, says Simon Menashy, investment director at MMC Ventures, which has invested £2.5m in Sky-Futures. Many oil and gas operators are interested in deploying drones on their platforms permanently, says Mr Menashy. “And there are 10,000 oil rig platforms in place around the world.” But as the industrial use of drones spreads, a question for operators will be how to navigate the vast amounts of data generated by fleets of flying robots.

In some ways, managing drone fleets will not differ from other fleets. After all, logistics companies have long used software to collect real-time data on trucks and other vehicles to devise fuel-efficient routes and faster deliveries. However, the type and volume of information drones can collect and transmit will demand new forms of data analysis.

“There’s one big difference in the operation of drones versus trucks, vans and taxis, and that’s the threedimensional element,” says Mr Ganzarski. “A drone doesn’t just go down a fixed road — it can fly anywhere and at any altitude.” Rising drone usage may not spell the end of other types of fleets. “You’ll see a lot of companies taking on drones,” says Mr Ganzarski, “not necessarily as the main vehicle, but as a supplement or part of a mixed fleet.”

Meanwhile, data management, emerging regulations covering the operation of drones and the need to take steps to ensure they fly safely will create new challenges for fleet managers.

This is not seen as a barrier to the growth of drone fleets, however. According to the Teal Group, a US-based research and analysis firm, global spending on the production of unmanned aerial vehicles — for both military and commercial use — will reach $93bn in the next 10 years. It is an industry with high-flying potential — in every sense.

See the full story in FT.com